by Charles G. Summers and Marilyn S. Diamond1

The

men and women who fought World War II have been

called “America’s greatest generation”.

They rallied to the cause without a moments thought

of their own safety. Many of these brave souls now

rest on foreign soil, or their remains, having never

been recovered, are remembered by inscriptions on

cemetery walls. For most, their personal story of

heroic action in the face of almost certain death

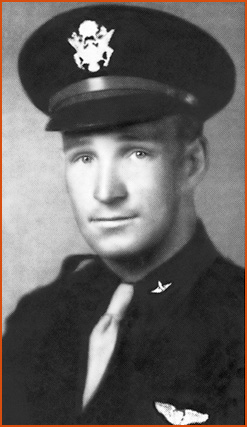

has never been told. Such is the case of 1st Lieutenant

Robert Simpson Blakeley. The

men and women who fought World War II have been

called “America’s greatest generation”.

They rallied to the cause without a moments thought

of their own safety. Many of these brave souls now

rest on foreign soil, or their remains, having never

been recovered, are remembered by inscriptions on

cemetery walls. For most, their personal story of

heroic action in the face of almost certain death

has never been told. Such is the case of 1st Lieutenant

Robert Simpson Blakeley.

Bob was born in Ogden, Utah on August 29, 1915

to Matthew and Artie Blakeley. Bob enjoyed hunting

and fishing in the Wasatch mountains that formed

the backdrop of their home. It was while exploring

these mountains that he developed his love of forestry,

a field that he had hoped to make his career. Bob

graduated from Ogden High School and then from Weber

College and the Utah State Agricultural College

(now Utah State University) with a degree in forestry.

Following the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl

Harbor, Bob’s sense of duty compelled him

to enter the fray and he joined the United States

Army on January 12, 19422. Following

basic training, Bob was sent to Luke Field, Phoenix,

Arizona as an Aviation Cadet-Pilot, and following

student pilot training was approved for transfer

to the Air Corps for fighter pilot training on May

29, 19423. He completed his initial training

in July of 1942 and was commissioned a 2nd

Lieutenant. While on furlough, he married Leah Geddes

on July 31, 1942 in the Logan L.D.S. temple. Immediately

following their wedding, Bob was transferred in

August to Dale Mabry Field, Tallahassee, Florida

and in September to Sarasota Army Air Base, Sarasota,

Florida4. At Dale Mabry, Bob received

extensive training in aerial combat in a P-40 ‘Warhawk’,

the aircraft he would fly in battle. Leah was by

his side until he was transferred overseas in early

October. Bob was assigned to the 57th Fighter Group

(FG), 65th Fighter Squadron (FS) as one of their

first group of replacement pilots since their arrival

in North Africa in July, 1942. Bob joined the 65th

FS on November 12, 1942 in Gambut, Libya (Bill Hahn,

personal communication), and was soon promoted to

1st Lieutenant.

Here we digress a moment to acquaint you with the

Fighter Group and Squadron with which Bob would

become comrades in arms. The 57th Fighter Group

was constituted on November 20, 1940 as the 57th

Pursuit Group and redesignated the 57th Fighter

Group May 15, 19425. On July 1, 1942,

pilots and aircraft (P-40s) left Quonset Point,

RI aboard the aircraft carrier USS Ranger. On board

were three squadrons, the 64th, The Black

Scorpions; the 65th, The Fighting Cocks; and the

66th, the Exterminators. When the Ranger was 100

miles off the African Coast, the pilots took off

and flew to Accra, Gold Coast. This was the first

fighter group to takeoff from a carrier in land

based fighter planes, and the entire group took

off successfully, the only such group to do so5.

They arrived in the Mediterranean Theatre of Operations

(MTO) on July 30, 1942, the first American fighter

group in African and the MTO, and the first American

Fighter Group to see action Europe5.

While space does not permit a more lengthy discussion,

the reader is referred to two excellent histories5,

6. For those interested in World War II history,

both are a must read. Since Bob’s military

records were lost in a fire at the National Personnel

Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri, little is

known of his exploits until the fateful day of April

18, 1943 when he participated in one of the greatest

aerial battles of World War II, the Palm Sunday

Massacre, aka Cape Bon Massacre. We do know that

Bob received the Air Medal, given to airman who

flew at least 50 missions of one hour or more. The

following excerpts are provided to give you some

idea of what life was like while serving in the

North African Desert. The importance of the North

African Campaign was summarized in the writings

of M/SGT Bill Hahn,6 “. . . if

we were not to overcome the Nazi drive to the Suez

Canal” and “should the canal have fallen,

and the Germans captured the oil fields of the Middle

East, we would never have recovered to defeat this

enemy.” Sgt. Hahn writes further, that life

in the desert consisted of “fighting flies,

heat, dust, disease, maggots, bloated bodies, and

lack or water. Ed (Duke) Ellington7,

a member of the 65th Squadron, writes, “It

is a really miracle that so many of us lived to

come home . . . The uncounted episodes regarding

the way we build heaters using 100 octane (fuel)

in a number 10 can filled with sand to heat food

or coffee. Washing clothes in 100 octane and hanging

them out to air dry. We were young, daring and disparate.

We did it all and lived to tell about it. The days

we ate from our mess kits and sand blew so hard

a crust formed over our food and we would tunnel

under the crust to get to the food.” These

excerpts barely scratch the surface of what our

men endured during that time (see reference5).

We now return to Lt. Blakeley and a fateful day

in April, 1943. The morning of April 18, 1943 (Palm

Sunday) dawned uneventfully over the desert. By

this time, the 57th had moved its operations westward

from Gambut, Libya to El Djem, Tunisia. Early in

the morning of April 18, the 57th flew a reconnaissance

mission over the Mediterranean and saw nothing8.

Later, the English and South Africans took their

turn and again reported no contact 8.

At 5:00 p. m., a final patrol by the 57th FG, consisting

of the 64th, 65th, and 66th, squadrons

left El Diem6, 8. Bob was one of 12 members

of the 65th to fly the mission that afternoon. Their

orders were, “Pick up Spitfire cover to be

provided by the 244 Wing RAF. Proceed to the Gulf

of Tunis and patrol easterly and westerly off Cape

Bon. Come back when gas supplies dictates”8.

They climbed out and leveled off at 16,000 feet.

They flew west along the coast line of Tunisia and

then turned out over the Mediterranean. They received

orders from Captain Jim Curl, Group Commander, and

executed a formation that now spaced them into the

sky like a flight of stairs8. They continued

patrolling, flying first to the east and then back

to the west. No enemy was sighted. As daylight turned

to dusk and gas ran low, they executed their final

turn to return to base when someone spotted a large

armada of aircraft below, barely 1,000 feet of the

surface of the water. It was composed of JU-52s,

a large tri-motored German transport, Me 109s and

Me 110s, both German fighter aircraft (Messerschmitts)

flying cover. The Germans were flying supplies and

reinforcements into North Africa. After sizing up

the situation, Curl gave the order to attack. “A

squadron leader somewhere in the formation said,

‘stay in pairs, boys,’ somebody gave

a yelp and there was a high-pitched howl as the

first line of four Warhawks split into pairs and

went down in a long sweeping turn to the right.

The second element followed. The German fighters,

turning into the attack from all directions, came

at the Warhawks. The Palm Sunday Massacre was on”

8. What happened next was a fierce, wild

battle, too confusing, too lengthy and too complex

for this treatise to describe. You are referred

to the excellent discussion presented by Dodds5

and Thruelsen and Arnold8. “Ten

minutes after the first shot was fired, the air

over the Gulf of Tunis was clear”8.

The Palm Sunday Massacre was over as quickly as

it had begun. During that ten minute battle, the

57th, and their top cover of spitfires, destroyed

59 JU-52s, 14 Me-109s, 2 Me 110s. In addition, one

JU-53 and one Me-109 were listed as probably destroyed,

and 17 JU-53s nine Me109s and two Me 110s were damaged.

The pilots who participated in the battle referred

to it as “the Goose Shoot”5.

At some time during that ten minute period, Bob’s

P-40 was hit by enemy fire and plunged toward the

Mediterranean. The following is the only known account

of what happened next. “One Warhawk pilot,

believed to be Lt. Blakeley of 65th squadron, bailed

out at K-6885 (map coordinate) and his a/c (aircraft)

hit the water at K-6284 (map coordinate).”

“A pilot (possibly Lt. Blakeley) was seen

swimming in the water. Sky conditions overcast,

visibility poor9”. In addition,

five other pilots from the 57th were listed as missing

in action9. “Air and ground searches

were conducted during the months of June, July and

October, but no evidence was found which would aid

in the locating and recovering of the remains of

the subject deceased (Lt. Blakeley)10”.

“ The coastal area has been searched for isolated

burial and sites of crashed planes with negative

results and QMG Form 371 for the subject deceased

(Lt. Blakeley) has been compared with the Reports

of Findings of Identification Processing Teams on

all unknowns washed ashore in that area, with negative

results”10. “Examination

of captured German documents failed to reveal any

information relative to the subject deceased (Lt.

Blakeley)”10.

Little did Bob realize that he had participated

in what would become know as one of the greatest

aerial battles of World War II5. The

destruction of the supply planes that day broke

the back of the Germans in North Africa and they

surrendered 25 days later8.

Bob is listed in Wayne Dodds book 8 as belonging

to the “Late Arrivals Club” (LAC). This

applied to pilots who failed to return to base following

a mission. Some returned days or even weeks later.

Unfortunately, such was not the case for Bob. The

names of all members of the 65th squadron are listed

on the wing of a Me-109 in the 65th “bar”8

which now resides in the New England Air Museum,

Windsor Locks, Conn., where an entire section is

devoted to the 57th Fighter Group. As was the custom,

Bob was listed as Missing in Action for one year

and one day then declared Killed in Action on April

19, 194411. He was posthumously awarded

the Purple Heart which was presented to his wife,

Leah. Bob is officially listed as Buried at Sea

on the Tablets of the Missing in North Africa, at

the American Cemetery in Carthage, Tunisia8.

As a modest man, Bob would be embarrassed by this.

He would say he was just doing his job, but to us,

he is a Hero.

We greatly appreciate the assistance of members

of the 65th Squadron for providing us

with information and leads: Bill Hahn, Ed Ellington,

Jim Hare, Ed Silks, and Lyle Custer. We also thank

Robert Johnston, Leon Jansen, and Dick Hewitt, all

WW II veterans.

1 The authors are the nephew

and niece of Robert S. Blakeley. Addresses: Department

of Entomology, University of California, Davis, CA

95616 and Honors Program, Weber State University,

Ogden, UT 84408, e-mail chasum@uckac.edu

and MDiamond@Weber.edu,

respectively. 2 National Archives and Records

Administration. United States Military Records Section.

3 Form 79 — US Army Medical Department.

4 Form AGRAC I-130, Identification Section,

Memorial Division, Army Air-Corps. 5 Dodds,

Wayne, S. [editor]. 1985. The Fabulous Fifty-Seventh

Fighter Group of World Was II. Walsworth Publishing

Co. Marceline, Missouri. 6 Hahn, W. 1959.

57th Fighter Group, 65th Fighter Squadron. Published

by the Author 7 Ellington, E. 2001. Uncle

Bud Newsletter. Vol. 4, No. 1. 8 Thruelsen,

R., and E. Arnold. Mediterranean Sweep. Duell, Sloan

& Pierce. New York. 9 Operational &

Intelligence Summary No. 96. Headquarters, Fifty Seventh

Fighter Group (AAF). Operations for April 18, 1943.

El Djem North L.G. 10 Lawing, W. F. Statement

of Investigation. 26 November 1948. US Army Air Corps.

11 Finding of Death of Missing Person.

War Department. The Adjutant General’s Office

Form No. 0353. 12 www.americanwardead.com/detailww.asp.

|